The Weird Portfolio

How To Avoid Bubbles, Limit Drawdowns, and Safely Grow Wealth

Introduction

This book describes an approach to investing that I developed for myself and I thought it might be useful for others.

It may not be for everyone. All investors have different risk tolerances and core beliefs. People are unique. This approach isn’t for everyone.

The portfolio utilizes six low-fee ETF’s to create an investment regime that is designed to deliver a satisfactory rate of return in multiple economic environments.

Like the title says: this portfolio is designed to avoid financial bubbles, limit losses during recessions/depressions, and safely grow wealth over a long period of time.

Each ETF represents an asset class. On their own, all of the asset classes are highly volatile. When lumped together in a portfolio, volatility is reduced and the portfolio still earns high returns. Because the asset classes all deliver returns during different environments, volatility is reduced and the portfolio delivers a consistent result.

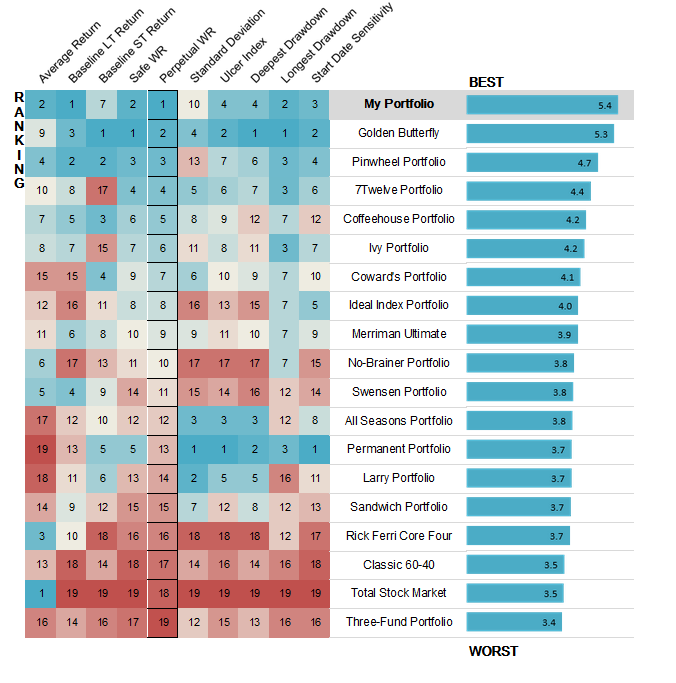

I’ll cut to the chase: these assets, when lumped together in a portfolio, deliver a return similar to owning 100% US stocks but with significantly less volatility and more shallow drawdowns. Most importantly: all of these asset classes are available to everyday investors in cheap and tax efficient ETF vehicles. You can jump right to the back-testing data at the end of the book to see these results.

However, the historical results aren’t the whole story. For this portfolio to continue to deliver results in the future, then these asset classes must continue their historical relationships. If these relationships don’t persist, then the portfolio won’t continue to deliver the fantastic results that it has in the past.

That’s why it is important to understand why these asset classes deliver their returns when they do. This book explains why I think that these relationships are likely to persist into the future. That’s what this book is all about, but you’re free to skip ahead and cut to the chase if you would prefer.

I would like to give a special shout out to the author of the Portfolio Charts blog, who was gracious enough to let me use his data for my back-testing. By far, his blog on asset allocation is one of the best resources that you will find.

Who I Am & Why I Wrote This Book

“The only true wisdom is knowing that you know nothing.” — Socrates

I’m not Warren Buffett. I’m not Stanley Druckenmiller. I am not a sage of investing.

I’m just an anonymous financial blogger and a corporate drone who tries my best to figure out what’s happening in the crazy world of finance.

In more practical terms, I’m trying to deploy my savings. My savings isn’t much in the grand scheme of things, but I take growing and protecting my savings very seriously.

I have been fascinated with investing since my teen years during the internet bubble in the late ’90s. I’ve been trying to figure this out for a long time, and I still struggle to do it.

Back in 2016, I started a blog where I tracked the actual performance of one of my brokerage accounts. In this brokerage account, I express my opinions about individual companies and the economic environment. My track record leaves a lot to be desired at the moment.

I often pick the wrong stocks, and I’m often wrong about the future. I put a lot of emotional effort into managing this account. The fruits of my efforts have mostly been the loss of hair.

I am a stubborn guy, so I keep trying and plugging away. I find the game fun, and it challenges me mentally. I enjoy it. Other people might choose a fantasy football team; I try to figure out the economy and which stocks will perform the best.

With that said, my results made me realize that I should develop an approach for most of my money that doesn’t try to predict the future because I get it wrong so often. I also wanted something much less stressful than owning 100% stocks. After all, the stock market has maddening levels of volatility and terrifying drawdowns.

A few years ago, I started to pursue financial independence, inspired by the likes of people like Mr. Money Mustache. I didn’t want to retire, but I wanted to have enough money to be a bit choosier about my time and mental energy.

To do this, I needed an approach to investing that is more reliable than my often-unreliable forecasts about the economy and individual stocks.

I also needed an approach that suited my personality. To put it simply: I am a pretty risk-averse kind of guy. I am not a sunny, cheery optimist who assumes everything will work out.

I often think in terms of worst-case scenarios. WebMD is a dangerous place for me. I know that the worst-case scenario won’t happen all the time, but thoughts of disaster always plague me.

I’m not what they call an “optimist.”

I’m not a doomsday prepper with a fully stocked pantry of emergency food rations and ammunition, but I’m always thinking of what could go wrong.

Risk-averse people like me often choose risk-averse investments. The most risk-averse investment is cash in a bank account, but that is a guaranteed loser over the long run. The interest on a bank account is never going to overcome inflation. Cash will gradually decline as inflation (which advances at roughly 2% a year) chips away at the purchasing power of money.

As for actual physical cash sitting in a safe — forget about it. If it’s earning no interest at all, then it’s guaranteed to lose over the long run.

Cash can be useful to deploy at opportune moments in the stock market, but an investor needs to accurately identify those moments. Warren Buffett has done this throughout his investing career. He accumulates cash when markets are frothy and then deploys it during bear markets. This is something that I attempt to do with my own money, but sadly, I am not 1/10 as good as Warren Buffett.

The only way to build wealth is by making money grow at a rate that exceeds inflation. Cash, therefore, is a guaranteed way to get crushed.

Sometimes people like me — who think in terms of worst-case scenarios all the time — get attracted to things like gold. Gold has been a safe asset for thousands of years of human history.

Gold has a lot of positive attributes (it’s a part of my investment approach), but the most an investor can expect from gold is to meet the rate of inflation over the very long run. With that modest return, gold endures tremendous volatility and terrible drawdowns. Gold lost 60% from 1981 through 1999, for instance.

So, if we want to make money, we have to take risks. There isn’t any way to completely get around that fact. Unfortunately, there is no such thing as return without risk. What risks should I choose? What would be an approach to investing that negates the need for a forecast but can reliably grow wealth over time?

One suggestion would be to buy a US market cap weighted index fund like the S&P 500.

If you can’t beat the market, the thinking goes, then obtain the average performance from the market.

This approach didn’t sit right with me, either. For starters, I know enough about market cap weighted stocks to see that it is expensive right now. When it gets expensive, it usually delivers low returns over the next decade or two.

I also know that the stock market can go through long periods where it does nothing but deliver agony.

There was a period from 1929 to 1954 (25 years), where the Dow Jones Industrial Average was flat. The market was also flat from 1966 to 1982 (16 years). In the 2000s, due to the tech wreck and the real estate bubble collapse, stocks did nothing. Stocks were flat for that decade but put investors through a high level of stress in the form of two nearly 50% drawdowns.

During the history of the US stock market, investors had to endure horrifying amounts of pain. There was an 80% drawdown in the early 1930s — a 50% drawdown in the 1973–74 bear market. There was also a 45% drawdown in the early 2000s, and a 50% drawdown during the 2007–09 financial crisis.

As for less catastrophic declines, they happen constantly. 10–30% declines happen all of the time, often without any reason.

On top of all of that pain, there are long stretches of time where stocks deliver no return. Imagine enduring all of that pain and then going through a 10- or 20-year period where you earn nothing. It has happened before and isn’t outside the realm of possibility for the future. This was the experience of American investors in the 1930s, the 1970s, and the 2000s.

Index funds also don’t sit right with me because I know that the experience of American investors — stocks usually go up and bounce back from declines — is unique.

In the rest of the world, stocks don’t always go up. The Japanese stock market, for instance, still has not returned to the highs of 1989. Imagine waiting 30 years, buying and holding, and not making any return on your savings but still going through massive drawdowns and pain.

For these reasons, I am not interested in buying and holding an index fund of US stocks. I realize this is the typical investment approach of most people who pursue financial independence, but it is not for me.

I also know that I am often wrong and often do a lousy job of predicting the future.

What is someone like me to do in this situation?

Traditional advice from people pursuing financial independence doesn’t resonate with me. I also don’t want to hire a financial advisor, as I don’t want to pay someone fees to do something that I can do myself. I also know that I am not the best at picking stocks and forecasting the economy.

I set out to develop a unique approach that would work for me. I wanted to design an investment strategy that could handle multiple economic environments, avoid lost decades, minimize drawdowns, and would negate the need for an accurate forecast about the future.

This approach would need to meet some critical criteria:

1) It wouldn’t need to predict the future.

2) It would be low cost.

3) It would be easy to implement. I don’t want to have to spend hours every week to adjust and hedge positions.

4) It wouldn’t rely on the genius of a manager whose genius can fade, or whose judgment can be affected by personal trouble.

5) It would have protection for all of the different kinds of economic environments that the world can throw at it — depressions, recessions, strong dollars, weak dollars, inflation, deflation, prosperity, or the disappointing ending to Game of Thrones.

6) I wouldn’t have to lose 45%-80% of my money every 15 years.

7) I wouldn’t have to endure long, lost periods (like 10–25 years) where I didn’t earn any return on my money.

8) I wouldn’t have to pay someone a lot of money to implement it.

9) The value of my money wouldn’t fluctuate a lot and stress me out.

I believe that I’ve developed a plan that meets all of these objectives. It’s how I invest my own money outside of my “speculative” account that I track on my blog where I go after the maddening pursuit of trying to outperform the market.

I thought I would share my approach because I felt that people needed to know that there is a different way to invest outside of mainstream financial advice. There aren’t many books that show an alternative path, so I thought I would write one.

Most books about investing recommend holding stock index funds forever and not worrying about the market.

Do stocks drop 50%? Have faith, and they will always return! For some reason, the authors take 250–500 pages to tell you this. It’s odd to me that the authors think their book was necessary when hundreds of investing books tell you the same thing.

This book takes a different approach. This book is an investment approach that I designed for myself. I think it offers a satisfactory return that meets my goals. I know this approach won’t make me fabulously wealthy, but I think it’s a sound way to invest money, grow wealth, and not have to chug Pepto Bismol when looking at the brokerage statement.

My approach isn’t for everyone, but it works for me. I thought it might resonate with people in a similar situation.

It might not resonate with you, and that’s okay. It’s a weird approach to investing. It uses controversial asset classes, like gold and small cap value. It has no weighting to US large cap market cap weighted index funds, which are foundational to most portfolios. It’s a weird portfolio. (This is my favorite part of the movie — when the title is awkwardly dropped.)

Anyway, even though this portfolio isn’t for everyone, I thought it might help some folks in a similar position to me. It might not be for you, and that’s okay. Everyone has a different personality, different goals, and different approaches to investing. There are many valid approaches to managing money, and there isn’t one true faith. The most crucial part is finding a plan that works for you.

Also, this is intended to be a short read. I’m a big believer that too many books about investing are too long when they are communicating a simple message. I do not understand why someone needs to write a 250-page $40 book that simply says, “Do not try to outperform the market and buy an index fund.”

I wrote this so people could breeze through it in a couple hours on Saturday afternoon. I get to the point and there is no filler. Hopefully, you find it useful and not a waste of your time.

Personal Finance

The focus of this book is on investing, not personal finance. This book outlines an approach to investing that works for me.

Of course, an investment strategy is meaningless unless a person actually has savings to deploy.

The reality is that investing is only a small portion of the battle. Saving money in the first place is the critical step in the process of building wealth. The importance of investing pales in comparison to the importance of personal finance. It took me a long time and some horrible experiences to realize this truth, but it is indeed the truth.

The core issue in personal finance is consistently spending less than you make.

If someone consistently spends more money than they make, they are going to accumulate debt. Debt has the damaging effect of making compound interest work against you. When compound interest is working in your favor, it snowballs over time and builds wealth. When compound interest works against you, it slowly ruins your life.

It’s hard to find an investing strategy that can achieve a 7% rate of return after inflation over the long run. Meanwhile, the average credit card interest rate is 18%. It is virtually impossible to find an investment strategy that will yield 18% over a long period, so someone paying this type of interest regularly is in a terrible situation.

Bill Burr once remarked that the mafia became irrelevant because their businesses became legal. He’s right. 18% is the kind of interest rate that mafia loan sharks used to charge degenerate gamblers in the 1950’s. Now, banks can do it legally thanks to the repeal of usury laws.

The average American has a credit card balance of $6,200. At an average interest rate of 18%, they’re paying $1,116 in interest a year. If that $1,116 could be invested every year into a strategy that yields 7%, in 30 years, that money would accumulate to over $100,000.

It’s also important to look at debt not in raw mathematical terms — but through the lens of the behavior which creates debt.

If a person’s debt is rising, then the person is living beyond their means and saving nothing. If someone makes a habit of living beyond their means, they are guaranteed never to accumulate wealth.

Debt isn’t a mathematical problem; it’s a problem of behavior. Debt can arise through no fault of the person — such as medical debt. In most cases, though, debt is a lifestyle choice and an American addiction.

It’s vital in this case to distinguish between needs and wants. In the United States, we find it hard to differentiate between the two. You need a roof over head and water to survive. You don’t need a new car. A $5,000 used car can get the job done just fine. You don’t need a big house. You need a place to live. You don’t need a premium cable package or the latest iPhone. A used model will do just fine. Get an HD antenna and a cord cutter cable package. You don’t need to eat at a restaurant every week. You can prepare a perfectly adequate meal in your kitchen for a few dollars. You don’t need to take on debt to go to an expensive private college. You can go to a cheaper state school. There are plenty of job opportunities in the trades or from fields that only require a two year degree.

Also missing from the discussion is an approach to happiness in general. When I was young, I used to think that wealth was about luxury and extravagant spending. Many rich people feel the same way, but none of that luxury brings them any happiness. Once a person meets an income that helps them achieve their basic needs, additional income doesn’t bring them any satisfaction.

A good exercise to figure out what’s really important in life is to make a list of all of the things in life that bring you joy. I’m willing to guess that most of these things are free.

What brings you joy in life? I’m willing to guess that they’re probably things like the time you spend with a loved one, a walk on a sunny day, or helping others. Your list is probably not stuff you can buy at a store. Buying the latest gadget or the smell of a new car provides only fleeting pleasure that quickly dissipates.

We like to spend money to get a dopamine rush. It gives a temporary feeling of pleasure. Money also unleashes our competitive impulses, which doesn’t do anything to increase happiness. Does it matter what our neighbor thinks of our car? Does it matter what a stranger thinks of our clothes? Does it really matter if people are impressed with our title at work?

As Americans, we have an unhealthy relationship with money. We see luxury as the end unto itself, and it’s just not true. We chase luxury with reckless abandon at the expense of things that matter and wonder why we’re miserable.

Material abundance is continuously increasing, and we push for it with reckless abandon.

The average home in 1960, for instance, was 1,300 square feet. Today, it is 2,700 square feet. They likely didn’t have a brand new car. They didn’t have iPhones, a big cable TV bill, a vehicle for every adult in the house. They lived a more straightforward, cheaper lifestyle. They were also happier. Talk to your grandparents and you’ll see this to be true. More stuff doesn’t make us any happier in life.

If money can’t buy happiness, then what’s the point of pursuing it?

The point, I think, is that money can buy a person’s freedom.

Here is a life that you can visualize. Imagine that you have no debt and don’t owe anyone on Earth a cent. You own your home outright. It’s not an extravagant home, but it’s all yours. You have an investment portfolio that generates a passive income for you year after year. You can work on your terms. You don’t have to answer to a boss. You have a cheap, paid for, car in the driveway. If your boss asks you to do something unreasonable, you can say no. If something breaks around the house, you have the cash to pay for it and don’t have to go into debt.

You own your time, and you have a lot of it. You can use this for money-making pursuits, but they are money-making pursuits that bring you joy and not a job that trades agony for money. Maybe you like to write books or volunteer. Perhaps you want to create art and sell it online. Whatever it is, you can pursue what makes you happy, and you don’t have to do unpleasant things to earn a living. You don’t have to do things that make you miserable until you drop dead.

That’s financial independence. That’s a goal worth pursuing. That’s not a car, a bigger house, or luxury.

True independence — true freedom — is worth striving for.

I’ll bet that a person in a simple situation of financial independence with modest spending is a lot happier than a high powered investment banker in Manhattan earning millions every year. The investment banker has to work 100 hours of work under constant stress and pressure to maintain their multi-million dollar luxurious lifestyle. They have to keep their kids in the most excellent schools, pay the mortgage on a $10 million penthouse, own a vacation home, buy the most beautiful suits, pay for incredible cars. None of it makes them happy, but they have to work continuously in something that brings them no fulfillment to maintain a lifestyle. They live a life of luxury, but they are not free. If they lose their job or take their foot off the gas, they can lose it all.

The goal, as I see it, isn’t to buy more stuff or increase prestige. The goal is to have enough money and a cheap enough lifestyle that you can do whatever you want. You want to own your time and energy.

Money isn’t about stuff — it’s about freedom.

I came to this truth through personal experience.

I entered my twenties with a very unhealthy relationship with money and life. I thought of money as a tool for pleasure and not as a tool for independence.

My life quickly descended into a hard-partying, hard-drinking lifestyle. I got addicted to alcohol and thought that going out and partying every night was a source of happiness.

It brought me no happiness, and it left me utterly miserable. The worst part is, it led me to accumulate a significant amount of debt.

By the summer of 2008, my life was a complete wreck.

I was out of college for a couple of years. I lost my first job and was a year into my new one. I had no savings and was sitting on a significant amount of debt. I was struggling to get by. I had no savings. My checking account would often go negative as I approached payday.

Lehman Brothers then collapsed, and it looked like the other banks are going to fall with it. The world economy and financial markets blew up spectacularly. Absolute terror gripped the world.

I always followed the markets closely, and at that moment I was aware that we might be facing the second Great Depression.

Meanwhile, I was facing the second Great Depression in financial shambles.

My credit card interest rates got jacked up to 30% as I digested what was happening to the economy. I was already down, and it got worse. Most of my income was being eaten up by interest.

Nearly 40% of my income was going to payments, and most of those payments were interest.

I also had no idea how much longer my job would last. What if my employer went out of business? What if I got laid off?

It was a horrible situation, and I’ll never forget how I felt. I felt desperate, and my life felt like it was out of control.

I thought of myself as someone who knew about money, but the truth was that no matter how much I knew about investing, I didn’t know anything about life. I didn’t understand that buying the coolest gadget or having a fun night out at a luxurious bar wouldn’t bring me any happiness.

At the age of 26, my life was a total and complete mess. I thought back to the person I was at 18. How full of optimism I was about the future. I felt like an actual failure in comparison to those ambitious dreams I made for myself.

I’ll never forget the way that this moment in my life felt. I felt hopeless, and I felt utterly broken as a person. I felt trapped and scared. The future was unknowable. Financially speaking, I was unprepared for what was unfolding. I was only 26 years old, and I already felt like a washed-up failure of a human being.

I vowed to end the situation. I vowed that I would never experience that kind of self-created mess ever again.

To save money, I took extreme measures, like renting out a cheap basement to live in. I did everything and anything to cut costs and minimize my expenses. I tried to spend no more than $50 a week on food, for instance.

I would often contemplate the mess I created for myself and ask myself questions like: “How could I have been so careless?” “Why was I so stupid?”

The truth was that it was the best thing that ever happened to me. It helped me become a more disciplined person. It took discipline that it took to get out of debt, save money, and end my addiction to alcohol.

I quit drinking and ultimately got out of debt. I took extreme measures to lower my expenses and live beneath my means. It ultimately paid off and I got out of the hole.

A key-person who helped me in my journey was the financial commentator Dave Ramsey. I have a different approach to investing than Dave — but that’s just details. Dave’s advice for getting out of debt helped me tremendously.

If you have a lot of debt, if you consistently spend more than you make, then my book about investing won’t be of much help. There is no way to get ahead if you can’t actually save any money.

If you have a lot of debt, you should probably read Dave’s book — The Total Money Makeover — which will give you simple and practical advice to pay off your debt and start to change your life.

I used Dave’s plan — the debt snowball — to get out of debt. He advocated listing debts in terms of amounts, not interest rates, and systemically paying them off, using the larger cash flows to reduce each larger debt. This strategy is mathematically unsound, but Dave’s insight is that debt has nothing to do with math. It’s about behavior and the debt snowball helps your attack debt in a behavioral way. Each victory over each debt balance gave me momentum. By the time I was finished, I felt victorious and I swore never to get into a situation like that again.

Dave also has some great, practical advice to stay on track. He recommends staying out of debt and having a cash emergency fund with roughly six months of expenses. The purpose of this is to keep you from going into debt to pay for an emergency (like a loss of a job or a major home repair). It also keeps you from dipping into your investments.

Many personal finance books focus on things like cutting $5 latte’s or other minor expenses. I like the Ramsey approach better. Go after your debt with a bazooka. Downgrade your house if it’s too much. Downgrade your car. Slash your grocery budget. No half measures. As he puts it, go on “beans and rice” until the job is done.

While Dave gives practical, step-by-step instructions for getting out of debt and establishing a strong personal finance foundation, I think there is a better book for changing your fundamental relationship with money. The book that accomplishes this goal is Your Money or Your Life by Vicki Robin and Joe Dominguez. While Dave’s book gives some excellent practical advice for getting out of debt and establishing a firm financial foundation, Your Money or Your Life provides a more philosophical approach to money.

The book shows the reader that money is not a source of happiness, but a tool to achieve freedom.

The book also contains an essential exercise. It recommends that you figure out how much money you have earned in your adult life and compare it to your net worth. For most people — including myself — this is a sobering and eye-opening experience. You’ll see how much money you’ve worked for in your life and how little you have to show for those efforts.

An excellent way to figure out your life’s earnings is to go to https://www.ssa.gov/myaccount/, which breaks down your income year by year.

The point of this exercise isn’t shaming. The purpose is to make it clear that we all have an unhealthy relationship with money and spending.

When you sit back at think about all the money you have wasted in your life — on overpriced cars, expensive meals at restaurants, gadgets gathering dust, overpriced drinks at bars — it puts into perspective how wasteful our lifestyles are. The point of the exercise isn’t to shame your past, but hopefully, help you develop a healthier relationship with money for your future.

It is only by establishing a healthy relationship with money that a person can move forward and stay out of debt and consistently accumulate wealth.

Once you’ve paid off your debts, are living beneath your means, and have a good emergency fund — then it’s the time to talk about investing. To get to that point, a healthy mental attitude towards money and life is necessary. Without that attitude and without the actions required to achieve that, then your investment strategy doesn’t matter.

Without this foundation, there isn’t much of a point to learning about investing. Without savings — without capital — it doesn’t matter what kind of portfolio you chose.

The significant muscle movement of personal finance is saving. A sustained and high level of saving isn’t possible if you don’t already have a healthy relationship with money. If you see money as a tool for pleasure and consistently live beyond your means, then you’re never going to save anything no matter how high your income is.

Once that foundation is established — consistent saving, consistent living below one’s means, a healthy attitude towards money — then that is the time to talk about investing.

So — how do we invest?

The Unknowable Future

When most people think about investing, they think in terms of “beating” the stock market.

There are two basic ways to attempt to beat the stock market:

1) Pick the asset classes that will perform best. Stocks or bonds? US Stocks or international stocks?

2) Pick the individual stocks that will outperform.

Both of these things are an attempt to predict what will happen in the future.

In the absence of a Flux Capacitor and 1.21 gigawatts of electricity, this is a difficult feat to accomplish.

Warren Buffett has focused on strategy #2. Buffett does this by finding stocks that are cheap relative to their fundamentals. He then tries to make a reasonable prediction about the future. He likes companies that have a “moat” to defend themselves from the competition while simultaneously earning large profit margins.

The most famous example of this is his investment in Coca-Cola. Buffett realized that Coke was an incredible global brand. People will buy Coca-Cola over a cheap store brand cola. Coke’s brand power allows Coca-Cola to charge more in price and earn a higher margin. Meanwhile, he also recognized that Coke could grow over time by expanding internationally.

Ray Dalio has focused on point #1. Dalio is adept at identifying where we are in a business cycle. Before the global financial crisis, he pivoted to asset classes — such as long term government bonds — that would benefit from the financial crisis.

Why not duplicate Buffett’s or Dalio’s methods?

The problem is, few investors succeed in picking stocks or choosing the right asset classes. There are plenty of people who have consumed Warren Buffett’s letters, but few that have been able to replicate his returns. Dalio has written much about his approach, but there are few investors who have been able to pivot to the right asset classes at the right times.

It would be nice if we had Dalio or Buffett’s skills and intelligence, but the sad reality is that very few of us do.

I attempt to do both, and my results are often unsatisfactory, even though I occasionally get something right. I chronicle these efforts at my blog. I find it fun and enjoy discussing my efforts with people on social media, but the reality is that I am no Warren Buffett or Ray Dalio.

Buffett makes picking stocks look easy. Find a moat and a margin of safety and bam, buy.

The problem is that this is extremely hard to do. Even Buffett makes mistakes, and his stock picks can turn against him. There are many examples of Buffett’s mistakes, but one that sticks out is his purchase of Dexter shoes in 1993. Buffett paid $433 million for the shoe company, which slowly became worthless as the company fought off cheaper shoes from low-wage countries.

Dalio gets things wrong, too. Dalio proclaimed that “cash is trash” in January 2020, shortly before the market collapsed due to COVID-19. Throughout the 2010s, Dalio also frequently compared the market environment to 1937, but the 1937-style market crash never arrived.

The future is hard to predict, even for the greatest investors of all time. The difficulty of prediction is a phenomenon studied carefully by Philip Tetlock, who observed that experts often fail to predict the future. Experts fail to predict the future even when equipped with high quality and confidential information. I highly recommend his book, Superforecasting.

If great investors like Warren Buffett and Ray Dalio make mistakes and everyone (including experts) are terrible at predicting the future, then what are the odds that you and I are going to get things right?

The simple conclusion is that the future is almost entirely unknowable.

Therefore, we face a unique challenge. We know that merely stuffing cash in a mattress or savings account is a guaranteed way to burn wealth over time. At the same time, we also know that it is challenging to pick the asset classes and stocks that will perform well.

For this reason, I set out to design a portfolio that keeps prediction to a minimum. My goal was to create a portfolio with different asset classes that would perform well in different economic environments without attempting to predict which economic environments will arrive.

What are some of these economic environments that are possible in the future? Here are some possible scenarios.

Inflation — The US Federal Reserve has been furiously creating money since the financial crisis. So far, this hasn’t increased the inflation rate. This money creation kicked into overdrive with COVID-19. Inflation begins to soar into the double digits in the 2020's, with no end in sight. To combat inflation, the Federal Reserve needs to increase interest rates massively. The increase in interest rates means that stocks should be valued less, and stocks fall. The interest rate hikes also lead to bond prices declining, as bond prices and interest rates are inversely correlated.

Deflation — The US faces a shock that the Federal Reserve can’t handle. Terrorists detonate a nuclear weapon at the heart of New York City. They launch smaller battles throughout the country, aided by sleeper cells. US economic activity plummets, and the country gears up for total war. Directly printing money will do nothing to revive a shell-shocked economy that is terrorized by fear. Deflation sets in, with the price of goods plummeting. The stock market crashes in reaction to these events.

Prosperity — The US enters a period of strong economic growth. Advances in technology, such as robotics and artificial intelligence, dramatically improve the productivity of US workers. Improvements in the efficiency and quality of production causes wealth to explode. The stock market continues to set all-time highs — US employment increases due to the bounty. Meanwhile, the technological improvements and advances in production keep inflation at bay.

Secular Decline — Decades of deficits finally catch up with the United States. The United States finds it difficult to sell bonds, and interest rates increase. The US dollar loses its place as the global reserve currency. The decline in the dollar’s value strengthens international markets at the expense of the United States economy.

The above scenarios represent a handful of situations that I can imagine in our unknowable future. I have no idea if any of them will happen and neither does anyone else.

I wanted to design a portfolio that would be able to handle all of these outcomes. I wanted a portfolio that could survive anything that the world could throw at it.

I wanted an iron portfolio with the resiliency to survive anything, but also one that could grow my wealth over time assuming that the global economy continues to grow over the long run.

I used to think that the way to do this was to choose the right stocks, but I soon realized that stocks are only a single asset class. I also realized the profound difficulty of selecting the right stocks in my attempts to beat the market.

I quickly realized that the way to grow wealth and control for different outcomes was asset allocation, as opposed to stock picking.

A phenomenon I observed, for instance, was that no matter what stocks I chose, once I owned enough of them, my portfolio of stocks would move in lockstep with the US stock market. It didn’t matter if the composition of my portfolio was entirely different from the overall US stock market; it still moved in tandem with the market. If the market crashed, then my portfolio would crash as well. Usually, my portfolio would crash more than the market.

I also realized that there were asset classes would do well if stocks went down. Why not own some of them as insurance?

I set out to create a portfolio of asset classes — as opposed to a portfolio of stocks — that would have elements that would survive the different economic environments in our unknowable future.

So, how do we do this? How do we design a portfolio that will be able to handle a different outcomes in an ultimately unknowable future?

The Trouble With Index Funds

It should be noted that when I refer to ‘index funds’ in this section that I am referring to a very specific kind of index fund: 100% US market cap weighted stocks. The portfolio I outline later in the book uses index funds, but applies them to different asset classes and segments of the stock market.

If the future is unknowable, and it is hard to predict, then what is the best way to invest?

When most people consider buying stocks without making decisions about the economy or stock selection, they turn to index funds. These are funds that charge low fees and own the entire stock market.

Buy an index fund, and you won’t outperform the stock market, but you’ll do average.

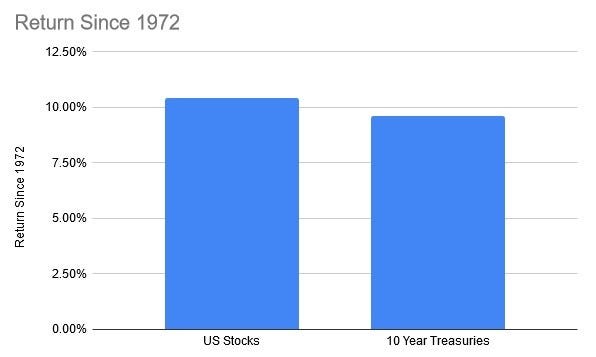

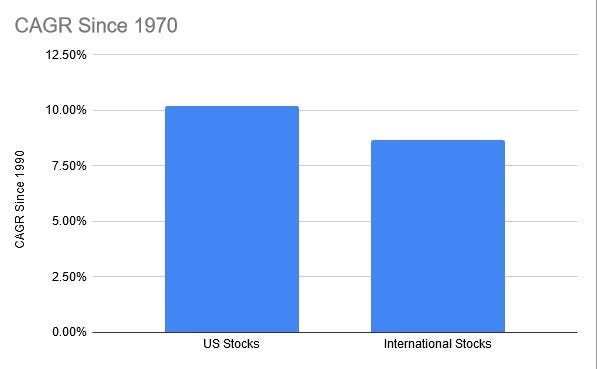

Over time, average returns in the stock market are quite spectacular. $10,000 invested in US stocks in 1970 would be worth over $1.1 million by the end of 2019. That is over a 10% rate of return.

Not only do US stocks perform well, but the theory behind an index fund is intuitive and easy to understand.

There are many participants in the stock market, attempting to make bets about which company will perform best. They talk to management; they research companies in depth; they pore over data.

All of these participants are trying to figure out which stocks will perform best in the future. Some investors succeed in doing this, but most do not. Research indicates that the typical active manager underperforms the market. The underperformance of active management is probably best documented in Burton Malkiel’s book, A Random Walk Down Wall Street.

The situation is worse because these active managers charge high fees, while an index fund is virtually free.

The math behind fees is pretty simple. Let’s say an investor opens an investment account with $10,000, earns a 10% annual return, and then contributes $10,000 to the account every year.

At the end of 30 years, this investor should have $1,809,434.25. However, if the same investor pays 1% a year in fees, that amount is reduced to $1,456,975.47. Fees cost this investor $352,458.78. They have only 80% of the money of our hypothetical index fund investor.

It’s also important to remember that most active funds underperform the market. This investor likely paid high fees and simultaneously earned a lower rate of return than the index investor.

The evidence is loud and clear: active management sucks. Active management consistently underperforms the market and charges too much in fees. Even if they could outperform, the fees of most active managers would eat into the high returns. Sure, there are stellar active managers — like Peter Lynch, Ray Dalio, or Warren Buffett — but what are the odds that you found the next Peter Lynch, Ray Dalio, or Warren Buffett?

Due to fees and the inability of active managers to outperform, index funds seem like a pretty good bet for a long term investor. Index funds charge low fees and deliver decent performance. It seems likely that corporate America will continue to grow earnings and sales, and an index fund investor can expect to share in those rewards.

So, why don’t I invest in US market cap weighted index funds?

I don’t invest in index funds for a few reasons.

1) I want to weight my portfolio towards cheap stocks and away from popular stocks.

When you ask an average person how an index fund works, they will likely say that the index is composed of the biggest companies.

How do we measure the biggest companies?

Most people think that the index tilts towards the companies that make more money.

Surprisingly, that is not how index funds work. Index funds are built based on market capitalization. Market capitalization is the number of shares multiplied by the price. In other words, index funds are weighted not based on any fundamentals, but simply based on what investors are willing to pay for the stock.

Market cap weighting leads to an interesting dynamic. Index funds purchase more of the stocks that are going up. As the price of a stock rises, the index systematically buys more of it.

In my view, this is the opposite of what an investor should do. An investor should buy undervalued companies. An undervalued company will likely have recently gone down. I want to weight my holdings towards companies that are a bargain.

The research shows that merely weighting a portfolio towards cheaper companies works very well.

From 1972 through 2018, owning small, cheap stocks (known as “small-cap value”), has delivered a 13.9% rate of return compared to the market’s 10.4% return.

In other words, small-cap value turned a $10,000 investment in 1972 into $5.2 million. The market would have turned the same investment into $1.17 million.

2) I don’t want to experience horrible drawdowns

US stocks delivered a 10% return since the 1970s, which is outstanding. However, during that period, they went through many horrible declines.

In 1973 & 1974, a $100,000 investment turned into $59,600.

From 2000 through 2002, a $100,000 investment turned into $62,930.

From November 2007 through February 2009, a $100,000 investment turned into $49,000.

In the most extreme example, from 1930 through 1932, stocks experienced a 80% decline in value. A $100,000 investment turned into $20,000.

It’s easy to look at a long-term chart of stocks and advocate that people “stay the course” and buy and hold, but it’s an entirely different experience when you are living through these drawdowns.

When a portfolio becomes large enough, these drawdowns are terrifying and painful. It’s one thing to have a $3,000 account and see it chopped in half. It’s a completely different experience when dealing with large sums. A $1,000,000 portfolio in 2007, for instance, turned into $490,000 by the bottom of the market in 2009. It is incredibly painful to live through something like that.

3) I don’t want to experience long periods of losses

US stocks can remain flat for long periods of time. Many people might think of the “long term” as 5 or 10 years. Unfortunately, the long term is longer than most people think.

From 1969 through 1979, in inflation-adjusted terms, the stock market declined by 13%. Would you want to save and invest for 10 years and lose money?

Another example of a lost decade is 1999 through 2009, a decade in which the stock market declined by 27%.

After the crash of 1929, the Dow Jones Industrial Average did not return to its previous high until the 1950's.

Needless to say, the long term isn’t 5 or 10 years. The long term is 30–40 years and stocks can lose money over periods as long as 20 years.

Meanwhile, these lost decades take place in the United States, whose stock market performed better than any other in the world.

For international investors, the experience is much darker.

The best example of this is Japan.

In the 1980s, the Japanese stock index grew six-fold.

During the 1980s, Japan was the envy of the world. It was the world’s best-performing stock market.

There was an excellent narrative to go along with this stock performance. Japanese companies were better and more disciplined, using novel methods of manufacturing, such as just in time inventory. Japan also had the most excellent education system in the world, producing the most intelligent and skilled workers. Japanese companies performed marvelously, and money poured into the Japanese stocks and real estate.

In 1989, Japan’s Imperial Palace was worth more than all of the real estate in California.

On December 29th, 1989, Japan’s Nikkei index peaked at 38,957.

The Japanese stock market has never returned to those highs. 30 years after the fact, the Japanese stock market has still not returned to those lofty heights experienced in 1989. The index currently stands at 20,750, 46% less than what it was at the 1989 peak.

The value today even obscures the depths of the crash in Japanese stocks. In 2003, the index was worth 8,057.61, a 79% decline from the peak in 1989.

Index investors advocate “buy and hold” for the long term. They say that you should hold stocks through thick and thin because it will always rebound. In the United States, that rebound can take a very long time. The worst-case scenario is the 22-year lull after the Depression. Less extreme, but still horrible, instances are lost decades like the 2000s and 1970s. Investors in other countries, such as Japan, have faced much more dire situations.

This knowledge of history is lost on investors who have been investing in the United States since the early 1980s. Investors since the early 1980s have been taught a simple lesson: buy every dip and stocks usually go up. Looking further back in history, this is not always the case.

In the worst-case scenario, an investor can experience a Japan-like experience, in which an entire investing lifetime can be lost.

I don’t want to experience horrifying 50% drawdowns. I don’t want to experience lost decades, and I want to pivot a portfolio towards sections of the market that are more likely to be undervalued.

For these reasons, I don’t invest in index funds. I have a different approach.

Asset Allocation

How do we prevent drawdowns? How do we avoid lost decades? More importantly, how can this be done in a way that will grow wealth over a long period and do so in a way that minimizes fees and taxes?

The answer, I believe, is in asset allocation.

The US stock market is only one ingredient in the vast menu of components available for an investor.

The world is full of different kinds of asset classes. The beauty of these various asset classes is that they all do well at different times.

There are asset classes that do well when US stocks suffer, like US treasury bonds. There are also asset classes that should perform well when US treasury bonds are doing poorly, like gold.

A portfolio of different asset classes can smooth out the returns and volatility of a portfolio, while still delivering a satisfactory performance over the long run.

We can build a portfolio that won’t go through the horrible drawdowns of a 100% US stock portfolio. We can also build a portfolio that can deliver a more consistent return than a single asset class, with no lost decades.

To do this, we need to look at some of the ingredients that are available for investors.

What are some of these ingredients?

Here are a few of the asset classes available on the menu:

Short term US treasury bills — This is debt issued by the federal government for short time frames. They provide a low rate of return, but the stability of principal.

Long term US treasury bonds — Long term treasuries are bonds issued by the federal government over long periods, such as 30 years. These bonds fluctuate more in price than short duration bonds because the interest rates can be volatile, but they are still backed by the full faith and credit of the United States government.

Investment-grade corporate debt — Investment-grade corporate debt is debt issued by large, stable corporations with a high likelihood of behind paid back. They should offer a higher yield than US treasuries, but with slightly more risk.

Junk-rated corporate debt — Junk-rated debt is also known as “high yield” debt. Junk is riskier debt issued by corporations that is on the more dangerous end of the spectrum. It typically offers a higher yield than investment grade but is more likely to default.

Foreign sovereign bonds — These are bonds issued by non-US governments. The bonds could be for developed countries, such as Japan or Great Britain, or they might be for riskier emerging markets (like India and China).

International developed stocks — These are stocks in developed countries like Japan or Europe.

Emerging markets stocks — These are stocks in countries earlier along in their development. They are growing faster than the developed world, but are also riskier because their economies can suffer more significant shocks.

Real estate — Real estate operates in a class of its own and delivers a return through rising property values and income paid on real estate investments.

Gold — Gold is an asset class of its own. It is the oldest asset class in the world. Countries and empires have risen and fallen throughout human history, but gold retains value. As an asset class, it is a controversial one, but it is the oldest store of value in human history.

Cash — Cold, hard, cash. You can either keep it in your wallet, in a bank account or a safe. It is guaranteed to lose money over the long run due to inflation. Still, it’s not going to experience significant drawdowns, and you can be reasonably sure that you will be able to use it for whatever you want. PJ O’Rouke said that “No government proposal more complicated than ‘this note is legal tender for all debts, public and private’ ever works.”

The above asset classes are only a small snippet of the asset classes available to the average investor. The beauty of all of them is that, like a US stock index fund, they can be accessed cheaply by anyone for a small fee. Anyone could open a brokerage account and buy all of these asset classes cheaply.

There are other asset classes that institutions and wealthy people have access to, like hedge funds, private equity, and venture capital, which aren’t available to ordinary people like you and me.

But that’s okay. Fancy asset classes don’t often do much better than basic asset classes available to everyday investors.

Warren Buffett famously made a bet with Ted Seides in 2007 that a cheap US index fund would outperform a basket of hedge funds.

Hedge funds have access to all of the fanciest strategies imaginable, but index funds still won the day. A big part of the reason is that rich people compete with each other chasing these strategies. A more significant reason is that these fancy strategies often come with an equally lavish fee, which digs into returns.

Hedge funds, for instance, often charge “two and twenty,” which means that they charge 2% of the total assets invested and take 20% of the profits. As most hedge funds underperform the market, this makes it a particularly painful way to invest.

Most rich people don’t want to invest in cheap asset classes for the masses, so they love these expensive and complicated choices. They like them because they’re exclusive. A rich person is accustomed to paying up for exclusivity — which often means higher quality in most arenas of life.

Financial professionals like complex vehicles, too, because a complicated investment scheme sells well. No wealthy person is going to pay someone to say: “Buy a diversified portfolio of cheap asset classes.”

What would be the point of that when it’s easy to do that on your own?

A rich person doesn’t want to drive a Honda. They want to drive a Ferrari.

Unfortunately for them and happily for us, investing isn’t a game where a higher price means better results.

I think we can do perfectly fine without messing around with the Ferrari’s of the investment world.

One of the most classic diversified portfolios available to average investors is the 60/40 portfolio: 60 % US stocks, 40% US bonds.

The performance of this straightforward portfolio — available to everyone at a low price — is outstanding.

Let’s take a look at a portfolio of 60% index funds and 40% in the 10-year Treasury bond.

From 1972 to 2019, this portfolio delivered a 9.6% rate of return, turning $10,000 into $815,000. That’s not as good as investing in the stock market alone, but this portfolio avoided the horrors like lost decades and 50% drawdowns.

In 2008, for instance, US stocks declined by 37%. This 60/40 portfolio lost only 14%. During the lost decade for US stocks of the 2000s, this portfolio delivered a 3.5% rate of return while US stocks were flat. It’s not a lot, but it’s a return that turned $10,000 into $14,115. It accomplished this result without the pain of two horrible drawdowns for US stocks: 45% from 2000–2003 and 50% from 2007–2009.

The portfolio does a great job of controlling horrible drawdowns.

Something particularly interesting about this portfolio is that it performs better than the sum of its parts.

Common sense tells us that we can expect the performance of the portfolio to mostly equal its weightings in the portfolio.

US stocks returned 10.44% from 1972 through 2019. 10-year treasury bonds returned 7.09%.

60% of 10.44% (the return on the stock market) is 6.26% and 40% of 7.09% is 2.84%. Add it up, and you get the expected return of the portfolio: 9.1%.

In the real world, something happens that is unexpected and very counter-intuitive. When rebalanced annually (an investor lets the portfolio run every year, then returns the portfolio to the 60/40 weighting at the end of the year), the actual return of the portfolio is higher than 9.1%. The real return of this portfolio is 9.6%. It’s not much of a difference, but it is still astounding: the portfolio adds up to a result that is greater than the sum of its parts.

Why does this happen? Why does this portfolio create a result greater than the sum of the parts?

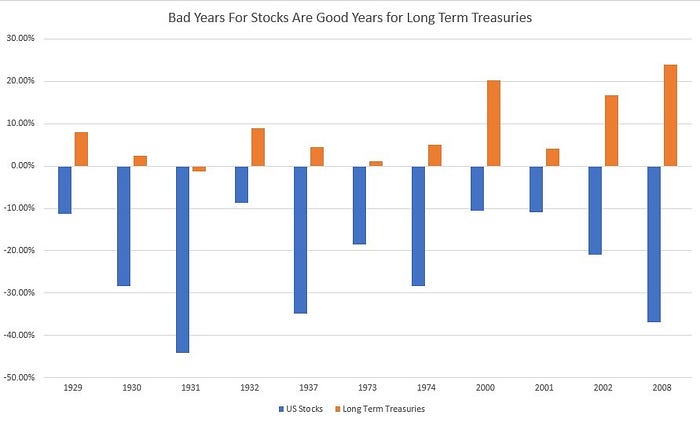

I think it happens because of the way that treasury bonds and stocks interact with each other. Treasury bonds do well when stocks do well.

When the portfolio is re-weighted, the investor is selling what went up and buying more of what went down. To meet the target of 60/40, they must regularly buy and sell the stocks and bonds to keep it in balance. The investor systematically buys low and sells high.

After a year like 2008, this investor would sell their treasury bonds and use the profits to buy more stocks. They are buying stocks when they are attractive. After a year like 1999, when stocks did incredibly, the investor is selling stocks when they are expensive and buying bonds.

Indeed, 60/40 is a terrific portfolio and an excellent introduction to the concept of asset allocation. It is also an approach that can be purchased cheaply via a mutual fund or ETF, so the investor doesn’t have to think about it.

With that said, I think we can do even better.

There are segments of the US market that have the potential of outperforming, like small value stocks. There are also asset classes that can do well when US treasury bonds under-perform. There are also segments of the US treasury bond market that perform best when US stocks do poorly.

Treasury bonds are also not guaranteed to be a “safe” investment class. When interest rates rise, for instance, the value of treasury bonds goes down. The principal of a treasury bond is also reduced in purchasing power if we experience inflation.

As I write this in May of 2020, the 10-year treasury only yields .63%. The low yield means that while the price will fluctuate over the next ten years, the investor will only earn a .63% rate of return.

US stocks are also costly at this moment and likely to deliver a low return over the next decade.

How do we know that stocks are expensive?

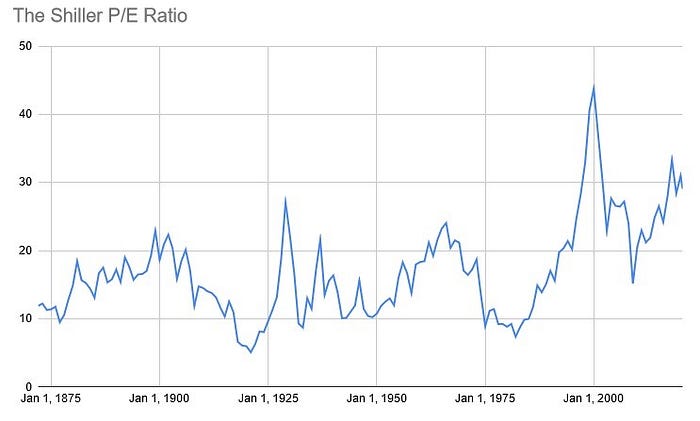

One method is the Shiller PE. The Shiller PE is a popular method of valuing the stock market based on the research of Robert Shiller, a Nobel Prize winning economist and historian. The Shiller PE takes the market’s total price and divides it by the average earnings over the previous ten years.

That PE currently stands at 29. For historical comparison, this is similar to the level in 1929 and at the end of the 1960s boom. In the late 1990’s bubble, the PE went up to an extraordinary level of 45.

What followed the bull markets of the 1920s, 1960s, and 1990s? Lost decades. Decades where stocks delivered no returns and a lot of misery.

I think it is likely we are about to experience another one of these lost decades in the 2020's.

By another metric — stock market capitalization to GDP — the stock market became the most expensive in history in January of 2020. This metric takes the total value of the stock market and divides it by the total economic output of the United States. In January of 2020, it was beyond the levels last experienced during the internet bubble.

Stock markets experience bull markets and lost decades because investors are continually shifting between periods of euphoria and despair, fear, and greed. Unfortunately, while the stock market grows over time, it doesn’t do so in a consistent way. There are always going to be long periods where it delivers nothing but pain, like the 2000s. There are going to be fast and furious bull markets, like the 1990s, when stocks advanced by nearly 400%.

My goal in creating a portfolio was to build something that would perform more consistently than US stocks and not experience such extremes in fear and greed.

I also wanted to create a portfolio that mostly avoided the issue facing US stocks and bonds: high valuations (stocks) and low yields (bonds).

Additionally, I wanted to access this portfolio in a tax-efficient manner, using vehicles that charge low fees.

The asset classes that met these goals for me were:

1) US small-capitalization value stocks. An asset class that invests in small, cheap stocks. This is sensitive to the broader economy and draws down significantly with the rest of the market during recessions and depressions, but it delivers a high rate of return over the long run. With that said, it doesn’t participates in a manias, such as the late 1990’s bubble. This is a high return (this is “offense”), but volatile, segment of the portfolio.

2) Small-capitalization international stocks. Small, international stocks. This is extremely sensitive to the global economy and experiences significant drawdowns. However, it offers a higher return than most international stocks (this is “offense”). It doesn’t participate in international stock manias, such as the Japanese bubble.

3) US real estate. US real estate via vehicles known as REITs offers a higher return than US stocks (this is “offense”). It does this because it consistently produces dividends and the value of real estate will increase over time with inflation. While it isn’t immune to bubbles, it enters bubbles less frequently than the overall stock market.

4) Foreign real estate. My goal with the “offense” elements of my portfolio was to not only invest in US assets, but to split equally between the US and the world for diversification benefits. For that reason, I split my real estate investments globally.

5) Long term treasury bonds. Treasury bonds tend to increase during periods of economic difficulty, making them the perfect “defensive” asset. Long term treasuries are the most volatile slice of the treasury market. They have the most extreme reaction to recessions. They tend to draw down more than other segments of the bond market when interest rates are going up. However, they also go up more than any other segment of the treasury market when interest rates are coming down, which is usually the case during recessions and depressions. For this reason, they are an excellent “defensive” element to a portfolio.

6) Gold. Gold tends to decline less than stocks during bear markets, while often remaining stable or even increasing. This makes it a good defensive asset during a stock drawdown, even though it isn’t as effective as long-term treasuries. Gold also tends to do well during lost decades for US stocks. Meanwhile, gold also helps balance out the risk of owning long term treasuries. Gold should do well during periods of time when long term treasuries suffer, such as inflation. Over the long run, gold tends to only deliver the rate of inflation, but it helps cushion drawdowns and perform well during periods when both stocks and long-term treasuries are weak.

These asset classes are all highly volatile on their own. When mixed a portfolio, volatility is reduced. Drawdowns are reduced. Lost decades are avoided. While there is no guarantee that these relationships will persist into the future, I think it makes logical sense that they should persist into the future.

In fact, when mixed together in a portfolio, the portfolio delivers an astonishing result. It delivers only a slightly lower return to owning 100% market cap weighted US stocks. Since 1975, this portfolio delivered real (after-inflation) results of 7.4%, while US stocks delivered 8.4%. This is astonishing because 40% of the portfolio is placed in defensive asset classes. It achieves these results with bond-like levels of a volatility, reduced drawdowns, and no lost decades. The worst year for the portfolio was a loss of 18%, compared to 37% for US stocks. Standard deviation for the portfolio was 11.5% vs. 16.6% for US stocks.

This happens because of the way that these asset classes interact with each other, helping create a more consistent rate of return.

To understand why they should persist into the future, we need to look into the nature of each asset class. We need to understand why they all deliver their returns. We need to understand when they deliver their returns. Once we understand that, we can better understand how they should interact with each other in a portfolio.

Small Cap Value

Why do market-cap-weighted indexes go through cycles of extreme bull markets and flat bear markets?

I think a significant reason is because of the way that market capitalization weighted portfolios are constructed.

Because indexes are buying more of the most popular stocks as they go up, the index is doubling down on the most expensive stocks. Meanwhile, indexes are systematically selling stocks that are going down.

Warren Buffett likes to say that investors should be “greedy when others are fearful and fearful when others are greedy.”

An index systematically does the opposite of this. It is selling the stocks that people are fearful of and buying the stocks that people like.

The best investors in history are known as value investors. They are attempting to purchase stocks for less than those stocks are worth. Value investors conduct in-depth research and try to ascertain whether or not those stocks sell for an attractive price relative to what that business is worth.

For those of us who don’t want to do in-depth research and spend all of our time researching stocks, is there an alternative to in depth and research-intensive value investing? Is there a way to systematically recreate the returns of the best investors of all time?

In the early 1990s, economists Kenneth French and Eugene Fama attempted to identify factors that lead to the out-performance of stocks. The determined “value” was a critical factor in returns.

“Value” was defined as stocks that trade at a low multiple versus the value of their assets and/or earnings.

French and Fama were attempting to replicate quantitatively what the best investors of the past did through analysis and research.

Their findings showed that purchasing large groups of cheap stocks, ranked by simple metrics of value, outperforms the market. They also discovered that “value” works best among smaller capitalization stocks. This makes sense intuitively. There should be more cheaper stocks in the smaller segments of the market.

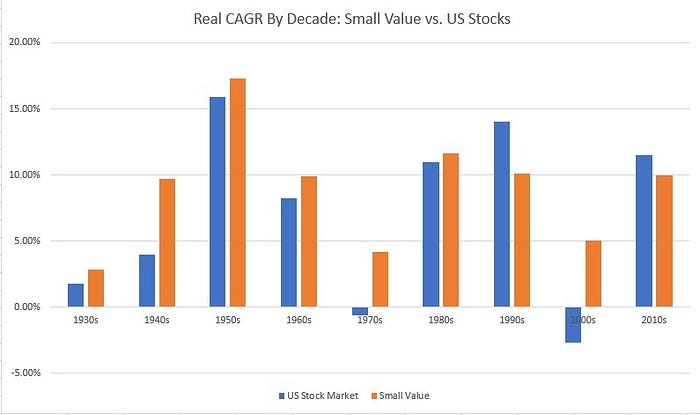

This asset class is called “small-capitalization value,” and it has a historical track record of outperforming the market as a whole. Since Fama and French published the paper in 1993, small-capitalization value stocks have continued to outperform, delivering an 11% return against a 10% return for US stocks.

I think this difference is understated, as that period includes the bubbles of the 1990s and 2010s.

My opinion on the 2010s is controversial, but I believe it was a large cap growth bubble much like the 1990s.

If we take the data back further to 1972, the difference between small cap value and US stocks is more extreme.

Small-cap value has delivered 14% from 1972 through 2019, compared to 10% for US stocks.

In other words, small-cap value turned $10,000 into $5.2 million, compared to $1.17 million for the US stock market.

Other quantitative investors have similar conclusions. One example is the book What Works on Wall Street by Jim O’Shaughnessy. O’Shaughnessy confirmed that all methods of statistical cheapness — price/sales, price/earnings, price/book, or sophisticated ratios like Enterprise Value/EBITDA — outperform buying a market-cap-weighted index of US stocks.

Why does this strategy work? How can a simple price ratio deliver out-performance? What causes this value anomaly, and will it work in the future like it did in the past?

The value anomaly is one of the most hotly debated questions in finance right now. It has turned into an existential problem for some.

Eugene Fama and Kenneth French argue that the out-performance of small-cap value is compensation for risk. Smaller companies are in a more vulnerable position than larger companies. Stocks that trade for cheap multiples are likely cheap for a reason. There is something wrong with the company that makes the market concerned. This means that the stocks may be riskier.

In markets, risk should be rewarded. The thinking is that smaller companies are more vulnerable and cheap companies are going through problems. By this logic, small cap value delivers a return because it is risky.

I think that risk is a part of the equation, but I also think that something else is at work.

When a stock encounters problems, the market tends to throw the baby out with the bathwater. Investors overreact. When a stock is doing well, the market will also reward it with an equally absurd multiple.

In some cases, of course, the stocks deserve these low multiples. Whenever I pull up a stock screener of stocks with cheap multiples, it is usually an ugly sight. You’re buying healthcare stocks in 2010 when the US is discussing healthcare reform that is endangering their profits. Right now, in 2020, these screens are filled with companies in the oil & gas sector, shortly after oil went negative during the COVID-19 crisis.

The market is sometimes right about these stocks. Often, these businesses are in significant trouble and will suffer a permanent impairment.

However, this isn’t always the case. Often, investors have overreacted and the cheap multiple is not deserved. When conditions return to normal for these companies, the multiples increase and the stock price goes up. A value investor purchases these stocks when the market is pessimistic about them and then sells when conditions have returned to normal and the stock price has increased.

Investors like Warren Buffett or Seth Klarman do this through intensive research and thought about the business itself. What Buffett and Klarman do is known as discretionary value investing.

Systematic value investing is different. An investor is simply trying to own enough of these companies to deliver a satisfactory result without trying to pick and choose which ones will do best.

The idea behind a portfolio of cheap stocks is simple. For some of the companies, the market will be right in assigning at a low price. However, for a majority of them, the market will have overreacted. By buying a basket of these stocks, an investor is taking advantage of market mispricings. The bad ones (also known as “value traps”) will go down. Meanwhile, many of the stocks in the portfolio will go up when their situation improves. In a portfolio, the net result is a gain for the investor.

Small-cap value tends to under-perform in fast and furious bull markets like the 1990s and 2010s. It tends to shine in flat markets like the 1970s and 2000s, when the overall market is working off a past period of excess.

While small value delivers a lower return than the market during bull run, the results are still pretty good. The performance is only poor compared to the overall stock market, which is usually experiencing a bout of euphoria that won’t last forever. Meanwhile, small value delivers a lower but perfectly adequate rate of return.

Small-cap value stocks have never experienced a lost decade in US history. I think this is due to the way that the asset class delivers its return. In flat markets and bear markets, there are always going to be out of favor stocks that will later be re-rated to a higher multiple. This is happening all of the time; no matter what the broader stock market is doing, decade after decade. For this reason, small value tends to deliver a more consistent return than US stocks. It doesn’t participate in bubbles, creating a greater consistency to returns.

My opinion about small-cap value is a controversial one. It is certainly possible that the “anomaly” won’t persist into the future.

Many are currently doubting the small-cap-value premium after the bull run of the 2010s in large cap growth stocks.

Of course, in the late 1990s, investors said the same thing. What happened after the 1990s?

While the indexes were negative in the 2000s, turning $10,000 into $9,700, small value delivered a 7.7% rate of return. This turned $10,000 into $20,977.

While the indexes needed to come down to Earth after the late 1990’s bubble, value stocks continued to do their own thing, delivering a distinctive return from the market.

An investor in a small-cap value strategy will lag the stock market during bull markets but should experience a more consistent return than market-cap-weighted US stocks over the decades.

With that said, small-cap value doesn’t offer any protection when the economy enters a severe recession and stocks endure a severe drawdown.

In 1973–74, for instance, small-cap value experienced a 40% decline. During the financial crisis of 2007–2009, small-cap value experienced a severe 56% decline.

Thus, I don’t want to rely on small-cap value alone as my sole source of returns. I think it deserves a significant place at the asset allocation table. I am willing to rely on historical data and make it the core of my portfolio’s strategy. I am even willing to take the unusual step and own small-cap value alone, without holding market-cap-weighted indexes at all.

However, while small-cap-value is the best form of offense in a portfolio, a portfolio needs a defensive strategy to protect the portfolio during severe drawdowns. I will explain the logic behind my defensive allocations in later chapters. My preferred defensive assets are long term treasuries and gold.

Additionally, I do not want to rely on small cap value as my sole source of “offense” in a portfolio. I believe that global diversification is necessary.

I also make real estate a core “offense” component of my portfolio.

International Investing

We live in a world that would be unimaginable to previous generations. You can hop on a plane and go anywhere on the planet quickly. You can take your phone out of your pocket and interact with people all over the world. You can quickly flip on a translator and translate emails and communications with people all over the world. Money can move around the globe at the click of a button.

The integration of the planet in the last fifty years has been truly unimaginable. The growth in global trade and communication has been a tremendous boon for humanity, with extreme poverty levels falling to all-time lows.

Thanks to all of this integration, international financial markets have also opened up to investors in the United States. Forty years ago, it was tough to invest overseas, and most US investors had to invest locally. American investors can now easily invest all over the world at the click of a button. It is a big blue world, and we don’t have to invest solely in the United States.

Unfortunately, the performance of international markets leaves much to be desired. Most US investors would have been better off avoiding the rest of the world. The track record of international investing isn’t particularly encouraging.

From 1990 through 2019, international stocks delivered a 4.6% rate of return, turning $10,000 into to $39,000. US stocks delivered a 9.9% return for the same time period, turning $10,000 into $171,600.

Of course, much of this atrocious performance has to do with the aftermath of the Japanese bubble. The Japanese stock market comprised a bulk of global stocks in 1990, and the deflation of that bubble adversely affected the performance of international stocks. In 1989, Japan was the largest stock market in the world. Japan’s stock index collapsed over the next decade and has still not fully recovered.

While international stocks as a whole delivered poor performance since 1990, there are segments of the international market that performed well.

Emerging markets are one example. Emerging markets provided a much higher rate of return since 1990, clocking in at 8.5%. This performance is not as good as the United States, but it is still much better than the overall international market.

The divergence between emerging markets and international investing as a whole shows how much of a drag the Japanese bubble was on returns when other segments of the global stock market did much better.

International stocks have a much better track record when viewed over a more extended period. Since 1970, foreign stocks delivered an 8.65% rate of return, which is much more respectable and closer to the return of US stocks.

It appears that returns were front-loaded in the 1970s and 1980s due to the Japanese bubble. In fact, from 1970 to 1990, international stocks outperformed the United States, delivering a 12.73% rate of return compared to 10.6% in the US.

An investor looking at the recent track record of international investing might want to give up entirely on the asset class, but a broader perspective reveals that international investing is better than it looks on the surface. While market cap weighting the world will likely lead to poor performance, there are segments of the international market that can deliver a satisfactory return.

I think it is vital to own foreign assets. International investments offer essential diversification benefits.

A key benefit of owning international stocks is currency diversification. Owning stocks in foreign currency is a nice counterbalance against owning stocks priced in dollars. If the dollar weakens, stocks priced in foreign currencies should strengthen.

An investor shouldn’t be overweight in a single currency. While the US dollar has remained a stronghold for most of the last century, this might not always be the case. Investors in other countries have experienced this first hand, such as Zimbabwe. Zimbabwe experienced rapid hyperinflation and eventually had to disband its currency entirely.

Another example of currency debasement is Germany in the 1920’s.

A loaf of bread in Germany cost 160 marks in 1922 and increased to 200 billion marks in 1923. The hyperinflation in Germany caused massive political instability and misery. It was this environment which allowed Adolf Hitler to take power, who plunged the world into a devastating war and unleashed unprecedented evil on humanity.

The currency collapse in Zimbabwe and 1920’s Germany are extreme examples that likely won’t happen in the United States, even though it is a remote possibility.

Even if such a currency collapse does not happen, there are still other reasons to diversify currency exposure due to the cyclical nature of the US dollar.

The US dollar goes through cycles of strength and weakness. When it is going through periods of weakness (such as the 1970’s and 2000’s), US markets tend to deliver poor relative returns. When the dollar is going through periods of strength (like the 1990’s and 2010’s), US markets tend to perform well. Owning stocks in different markets can diversify these cycles and reduce exposure to a single currency, reducing the risk of a portfolio.

Another critical element of international investing is political diversification. Throughout the 20th century, the US was the best place to invest. The US has sound regulations and a free market. Contracts are strictly enforced, and property rights maintained. We have the world’s reserve currency. The US navy defends sea routes and trade arrangements without the world. As the largest economy with the world’s largest military, it is the dominant power and the dominant economy.

While the US has been the most attractive environment for capital, will that always be the case in the future? Could our political environment fall apart? It’s hard to imagine how US supremacy could fall apart, but it can happen, and a balanced portfolio ought to be prepared for this possible outcome.

The possibility of the US falling apart politically is not zero. Political risk is real. International investing helps diversify this political risk. Even if the US falls apart politically, there should still be other countries that will stay strong. I think it makes sense to spread political risk across the globe. Some countries will win, some will lose. If an investor exposed to all of them, it diversifies the bets and guards against a permanent loss of capital, which investors in countries like Russia and China experienced when they fell to Communism.